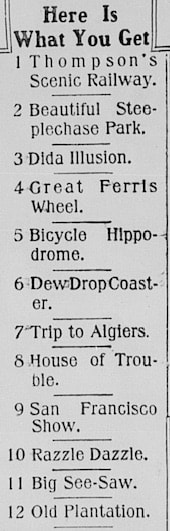

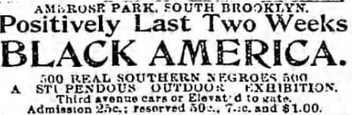

In researching my new Coney Island webinar (aka Coney Island virtual tour), I've delved deep into the influences on this famous amusement zone, notably the midways at various world's fairs. The 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo--a major city back then!--was a significant influence on Coney, since that's where Skip Dundy and Frederic Thompson became "Mighty Men of the Midway," designers and operators of an enormous range of attractions. The photo (via the fantastic Doing the Pan site) here focuses on the Aerio Cycle, a Thompson-devised mechanical fun device, which he had invented for a previous World's Fair, the Tennessee Centennial in Nashville, and would eventually make its way to Coney Island. But it's hard not to notice, stage left, Old Plantation, a very popular--and blatantly racist, albeit not by 1901 majority standards-- attraction, for which Thompson and Dundy were also responsible. What was Old Plantation? Thanks to the Uncrowned Queens Institute for Research & Education on Women, Inc. and its Uncrowned Community Builders Project, which focuses on the Black history in Western New York, we learn that the Old Plantation tried hard to recreate the pre-Civil War South, including "cotton and corn fields with real growing crops and slave cabins." One contemporary description said the attraction required the "services of 250 genuine southern cotton field Negroes in the portrayal of life on the plantation," while another called them "darkies who vary in age from tiny pickaninnies to white-headed uncles and aunties." Nightly minstrel shows, the Uncrowned project tells us, depicted scenes from plantation life, with performances by singers, banjo players, dancers and "Laughing Ben," a 96-year-old former slave. That means he was born in 1805 and, likely had spent nearly two-thirds of his life enslaved. That's ugly stuff, and a reminder of the palpable legacy of slavery.  What happened at Coney Island? Many attractions from Buffalo came to Coney Island, notably Luna Park, the stunningly advanced amusement park that Thompson and Dundy opened in 1903. But none of the Luna Park advertisements I found mentioned Old Plantation, so I suspect it didn't move to Brooklyn from Buffalo. Still, they apparently tried. A Nov. 23, 1902 article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, previewing the amusement park under construction, said: "The romance of life in the Sunny South before the war will be portrayed in a reproduction of an an old plantation, showing scenes in the cotton fields and the old time darky pastimes and dances." Of course, it was not much of a "romance" for the people who were enslaved, and it's awful to think the majority culture took pleasure in it. Moving to Steeplechase A few years later, however, Steeplechase Park, a rival amusement park, was advertising Old Plantation as one of several attractions. See the excerpt at right from a Steeplechase advertisement in the June 30, 1906 New York Evening World, and look at the bottom. Old Plantation was presented as simply one of many Steeplechase features, including the ferris wheel, the "Big See-Saw" (the updated version of the Aerio Cycle), and the Razzle Dazzle. It's unclear if Old Plantation lasted past a year or two. The sole contemporary account I could find was from the June 30, 1907 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which quoted a Steeplechase representative as saying, "In the performance called 'The Old Plantation,' the performers are all negroes, and some of them are very clever. They are professionals, having played with Williams and Walker and other colored stars." (That's a reference to the acclaimed vaudevillians George Walker and Bert Williams, cited in this essay for aiming "to tweak the popular music idiom of the day—which was dominated by a derogatory genre known as 'coon songs'—to render such songs either benign or ironic.")  A troubling history It didn't start with Old Plantation. Consider the image at right from the July 2, 1895 edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Even before the amusement parks emerged, during a time when circuses put "exotic" people on display, an exhibition was marketed of "Black America," with "500 Real Southern Negroes." (That was in "South Brooklyn," which at the time was considered the area around Gowanus/Sunset Park; in this case, Ambrose Park was at Third Avenue and 37th Street. Brooklyn initially was the central-west town, later city, within Kings County.) In the New York Times, Sam Roberts wrote a 2014 article about this phenomenon, noting that there's no record of any objection at the time. One headline at the time, he noted, cited the “Fun-Loving Darky of Old Slavery Days.” Interestingly enough, the promoter--according to researcher David Fiske--aimed to show "the better side of the colored man and woman of the South,” emphasizing their musical talents. Fiske notes that white locals were encouraged to visit Black America by their pastors, and it was, according to one 1947 article, “a first effort to make some presentation of the Negro as a person." That said, Fiske wrote that the absence of whites in the cast meant the absence of slavers: "Black America served not as a documentary of the life of blacks on antebellum plantations, but as a showcase of the talents and versatility of black people." Around the turn of the century, in fact, the brand name Old Plantation was used to sell both coffee and peaches, according to advertisements I found. Unfortunately, there's not a huge gap between that and the long-running brand of Aunt Jemima, whose operators only this year recognized they needed to stop profiting from racist stereotypes.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Touring Brooklyn BlogObservations and ephemera related to my tours and Brooklyn. Comments and questions are welcome--and moderated. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed