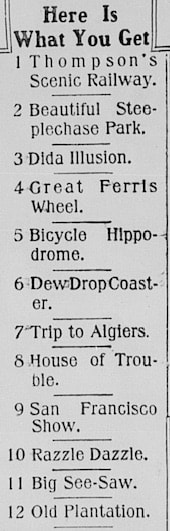

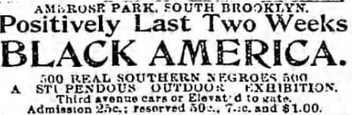

In researching my new Coney Island webinar (aka Coney Island virtual tour), I've delved deep into the influences on this famous amusement zone, notably the midways at various world's fairs. The 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo--a major city back then!--was a significant influence on Coney, since that's where Skip Dundy and Frederic Thompson became "Mighty Men of the Midway," designers and operators of an enormous range of attractions. The photo (via the fantastic Doing the Pan site) here focuses on the Aerio Cycle, a Thompson-devised mechanical fun device, which he had invented for a previous World's Fair, the Tennessee Centennial in Nashville, and would eventually make its way to Coney Island. But it's hard not to notice, stage left, Old Plantation, a very popular--and blatantly racist, albeit not by 1901 majority standards-- attraction, for which Thompson and Dundy were also responsible. What was Old Plantation? Thanks to the Uncrowned Queens Institute for Research & Education on Women, Inc. and its Uncrowned Community Builders Project, which focuses on the Black history in Western New York, we learn that the Old Plantation tried hard to recreate the pre-Civil War South, including "cotton and corn fields with real growing crops and slave cabins." One contemporary description said the attraction required the "services of 250 genuine southern cotton field Negroes in the portrayal of life on the plantation," while another called them "darkies who vary in age from tiny pickaninnies to white-headed uncles and aunties." Nightly minstrel shows, the Uncrowned project tells us, depicted scenes from plantation life, with performances by singers, banjo players, dancers and "Laughing Ben," a 96-year-old former slave. That means he was born in 1805 and, likely had spent nearly two-thirds of his life enslaved. That's ugly stuff, and a reminder of the palpable legacy of slavery.  What happened at Coney Island? Many attractions from Buffalo came to Coney Island, notably Luna Park, the stunningly advanced amusement park that Thompson and Dundy opened in 1903. But none of the Luna Park advertisements I found mentioned Old Plantation, so I suspect it didn't move to Brooklyn from Buffalo. Still, they apparently tried. A Nov. 23, 1902 article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, previewing the amusement park under construction, said: "The romance of life in the Sunny South before the war will be portrayed in a reproduction of an an old plantation, showing scenes in the cotton fields and the old time darky pastimes and dances." Of course, it was not much of a "romance" for the people who were enslaved, and it's awful to think the majority culture took pleasure in it. Moving to Steeplechase A few years later, however, Steeplechase Park, a rival amusement park, was advertising Old Plantation as one of several attractions. See the excerpt at right from a Steeplechase advertisement in the June 30, 1906 New York Evening World, and look at the bottom. Old Plantation was presented as simply one of many Steeplechase features, including the ferris wheel, the "Big See-Saw" (the updated version of the Aerio Cycle), and the Razzle Dazzle. It's unclear if Old Plantation lasted past a year or two. The sole contemporary account I could find was from the June 30, 1907 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which quoted a Steeplechase representative as saying, "In the performance called 'The Old Plantation,' the performers are all negroes, and some of them are very clever. They are professionals, having played with Williams and Walker and other colored stars." (That's a reference to the acclaimed vaudevillians George Walker and Bert Williams, cited in this essay for aiming "to tweak the popular music idiom of the day—which was dominated by a derogatory genre known as 'coon songs'—to render such songs either benign or ironic.")  A troubling history It didn't start with Old Plantation. Consider the image at right from the July 2, 1895 edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Even before the amusement parks emerged, during a time when circuses put "exotic" people on display, an exhibition was marketed of "Black America," with "500 Real Southern Negroes." (That was in "South Brooklyn," which at the time was considered the area around Gowanus/Sunset Park; in this case, Ambrose Park was at Third Avenue and 37th Street. Brooklyn initially was the central-west town, later city, within Kings County.) In the New York Times, Sam Roberts wrote a 2014 article about this phenomenon, noting that there's no record of any objection at the time. One headline at the time, he noted, cited the “Fun-Loving Darky of Old Slavery Days.” Interestingly enough, the promoter--according to researcher David Fiske--aimed to show "the better side of the colored man and woman of the South,” emphasizing their musical talents. Fiske notes that white locals were encouraged to visit Black America by their pastors, and it was, according to one 1947 article, “a first effort to make some presentation of the Negro as a person." That said, Fiske wrote that the absence of whites in the cast meant the absence of slavers: "Black America served not as a documentary of the life of blacks on antebellum plantations, but as a showcase of the talents and versatility of black people." Around the turn of the century, in fact, the brand name Old Plantation was used to sell both coffee and peaches, according to advertisements I found. Unfortunately, there's not a huge gap between that and the long-running brand of Aunt Jemima, whose operators only this year recognized they needed to stop profiting from racist stereotypes.

0 Comments

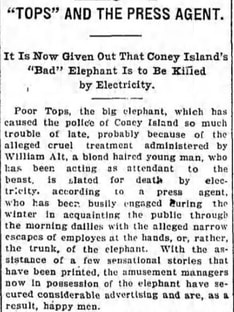

In researching my first Coney Island webinar (aka Coney Island virtual tour), about Coney up through the 1920s, I delved into the story of Topsy, the elephant that was unfortunately put to death in public in early 1903. As we now know, elephants are soulful animals, and it's wrong to force them to perform in circuses, especially given the cruel techniques used to "train" them. But they didn't know that at the turn of the 20th century. Articles in the local press, like the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, referred to Topsy as a "Bad Elephant" or an "Angry Elephant." The latter was surely true, though the former less so: Topsy was angry for a good reason: she was regularly maltreated by his handlers, so much so that he killed a man. But the Dec. 13, 1902 Eagle article I've posted at right serves as an astonishing form of media criticism, and is--especially compared to other coverage--much more sympathetic. "Poor Tops," we're told, has caused the police "so much trouble of late, probably because of the alleged cruel treatment" by her attendant. The Eagle describes how a “press agent has been busily engaged" with tales employees narrowly escaping the elephant's purported wrath. "“With the assistance of a few sensational stories that have been printed," the article notes, " the amusement managers now in possession of the elephant have secured considerable advertising and are, as a result, happy men.” This is pretty sophisticated analysis of the way media stories often emerge, shaped by public relations people--"press agents," back then. And, yes, the next step, Topsy's ugly execution, was very much a media event, too. A new New York City report on furthering fair housing in New York aims, in the words of the press release, "to break down barriers to opportunity and build more integrated, equitable neighborhoods." Key goals of the plan include:

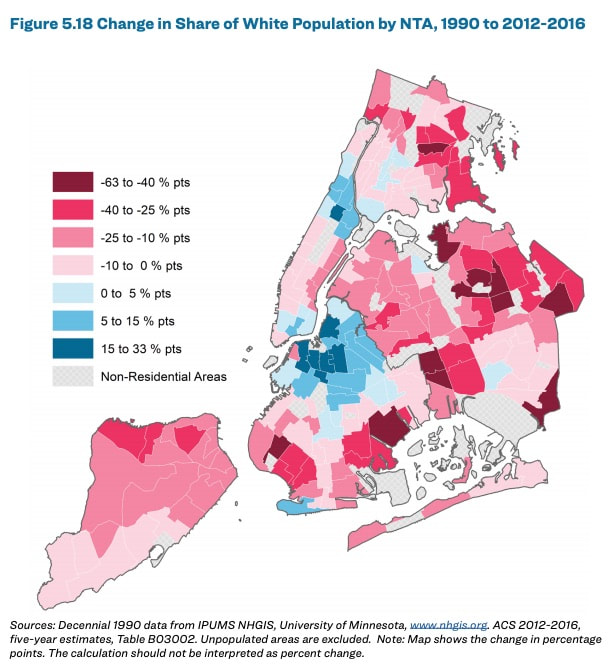

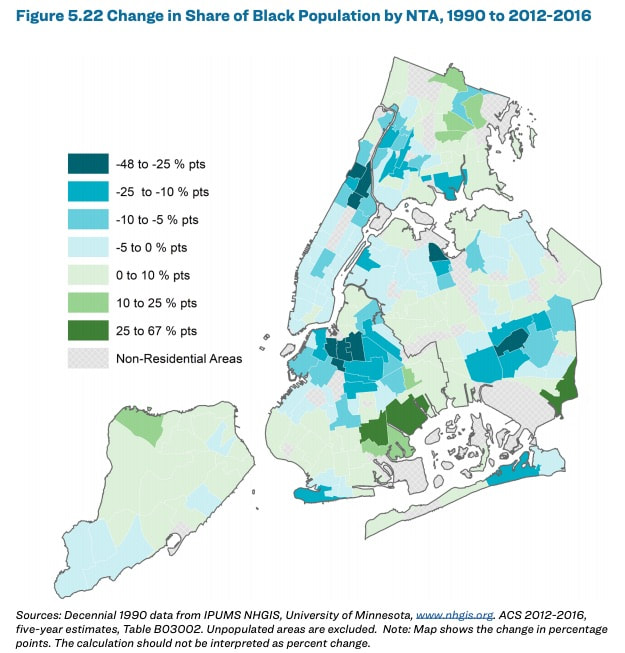

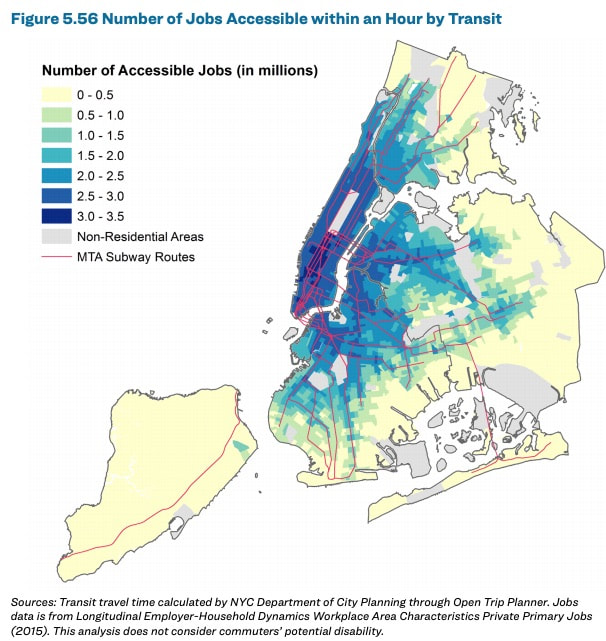

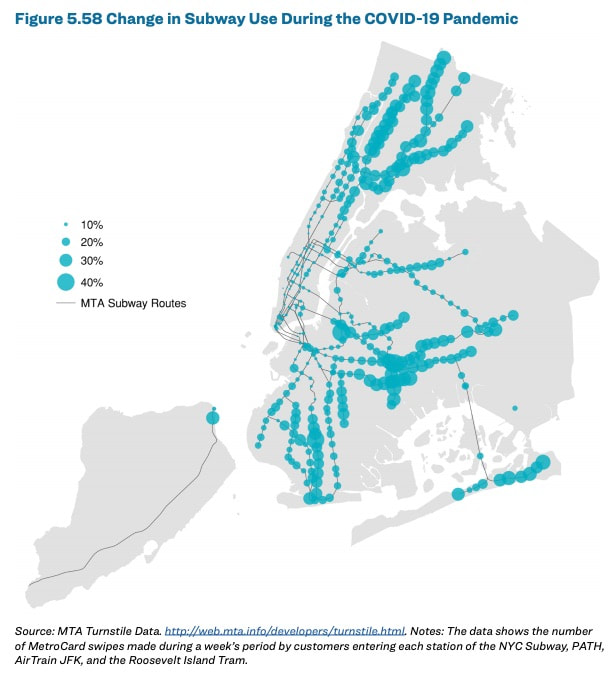

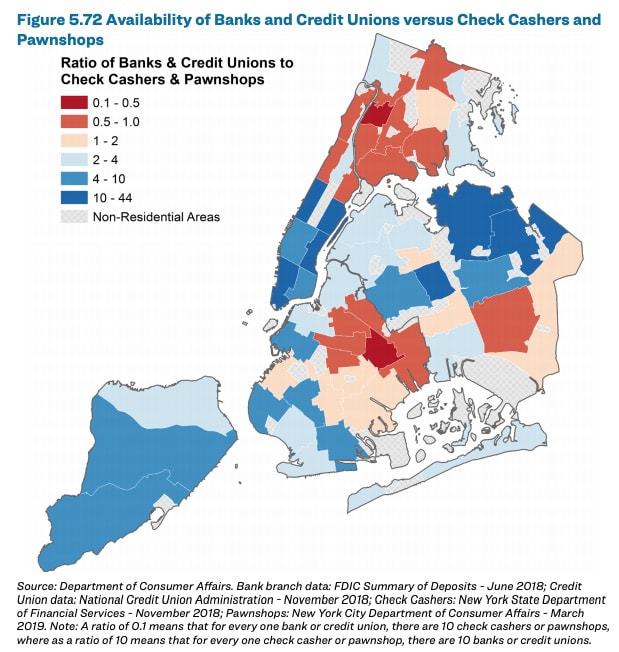

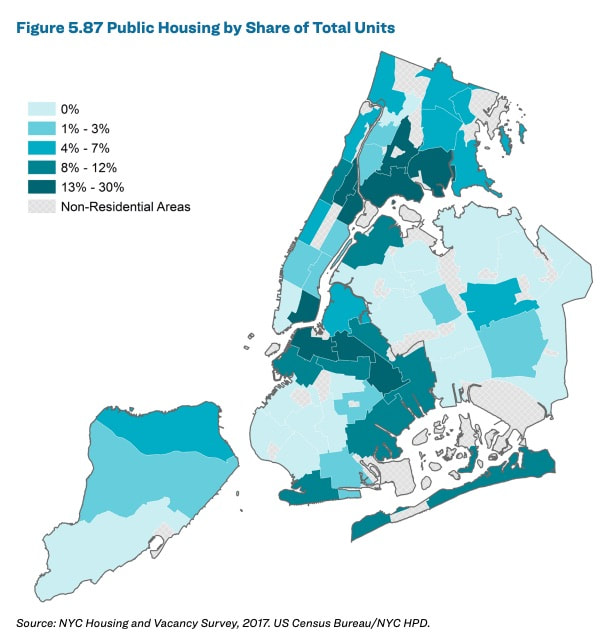

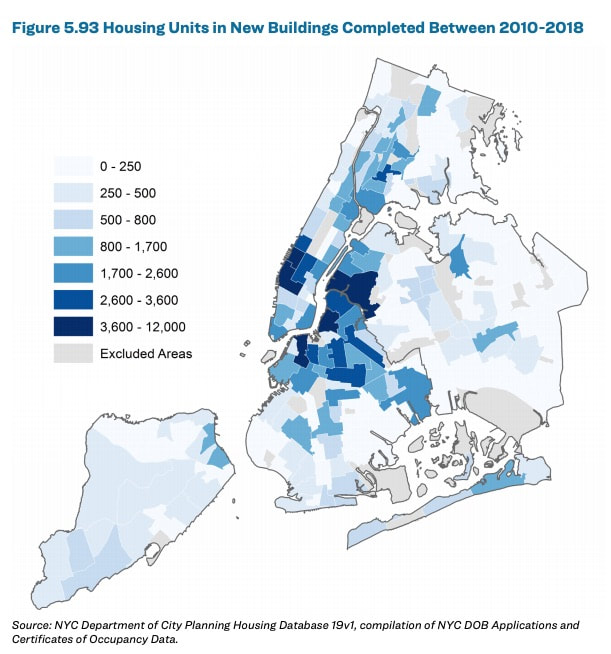

Below, I've highlighted a few graphics from the plans especially relevant to Brooklyn, with signs of gentrification; a shift in the black/white population in Central Brooklyn; a notable reliance on essential workers who commute long distances (such as from southern and eastern Brooklyn); a notable absence of public housing in southwest Brooklyn; a concentration of new construction in hot areas like Williamsburg and Downtown Brooklyn. A recent article from London-based Time Out magazine on The 40 Coolest Neighbourhoods in the World (note the British spelling) listed Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn as #4, noting that it's "cloaked in history," but this year "became New York’s greatest incubator of the future," given its role as a main hub for Black Lives Matter protests and the home to mutual aid networks.

I always resist such lists, because 1) "Cool" can be very arbitrary, and 2) the evidence cited is inevitably partial, unable to take in the vastness of a neighborhood, especially one as large as Bed-Stuy, with many layers to it. That said, this has been an important year for Bed-Stuy, as the listing notes. I'd add, for example, The Billie Holiday Theatre's production of 12 ANGRY MEN…AND WOMEN: THE WEIGHT OF THE WAIT (and this shorter interview). The Time Out article links to two, more in-depth articles. One, headlined This local group is supporting Bed-Stuy's Black community through fundraising and block parties, concerns Building Black Bed-Stuy, which is raising capital for three enterprises: Life Wellness, The Watoto Free School, and The Black Power Blueprint. (Here's more, from Vogue, on Building Black Bed-Stuy.) That first linked Time Out article article also lists five spots for outdoor dining, all of them relatively new restaurants and not necessarily Black-owned. (Here's a link to a standalone dining list.) The second link from the main article reads Get to know the best Black-owned businesses with our Bed-Stuy area guide and states, "Bedford-Stuyvesant is a historic Brooklyn neighborhood that's alive with wonderful Black-owned businesses and a tight-knit community." Indeed, it advises "Shop Tompkins Avenue and support Black-owned businesses like Bed-Vyne Wine & Spirits, Peace & Riot, Sincerely, Tommy while sipping on a drink from Brooklyn Kettle." A surprising link to my tour It also advises that, "On a Sunny Day," "Take the New York Like a Native Bed-Stuy Walking Tour, where you'll learn about the history of the neighborhood." That's a nice plug, but it's also be misleading, because I'm not a "Black-owned business" nor ever professed to be one. (The mention in Time Out was a surprise.) Nor am I a Bed-Stuy local--just as I'm not a resident, present or past, of most of the neighborhoods where I lead tours. (Or, well, have led tours for 20 years. Since March, the walking tour business has pretty much been on hold.) But I've spent enough time walking and studying the neighborhoods where I do lead tours to offer insights and context. I don't think a web search would find another tour guide/company that lists tours of Bed-Stuy, but I know that Suzanne Spellen and Morgan Munsey, a team of guides (both African-American), lead occasional tours of the neighborhood for the Municipal Art Society and can do so privately. See Spellen of Troy. Another Time Out link leads to Six secrets of Bedford-Stuyvesant, "the historic and tightly-knit Brooklyn neighborhood." Well, Bed-Stuy can be tightly-knit, but, given that it had more than 155,000 people (larger than Albany or Syracuse) in 2018, the generalization is unwise. But the article usefully cites the Hattie Carthan Community Garden, the Billie Holiday Theatre, and other neighborhood features. |

Touring Brooklyn BlogObservations and ephemera related to my tours and Brooklyn. Comments and questions are welcome--and moderated. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed